Visitors watch the "World Without Ice" multimedia installation in Michigan Tech's McArdle Theatre in late September 2015. (Photos by Keweenaw Now)

"Nearly 200 nations have assembled here this week -- a declaration that, for all the challenges we face, the growing threat of climate change could define the contours of this century more dramatically than any other. And what should give us hope -- that this is a turning point, that this is the moment we finally determined we would save our planet -- is the fact that our nations share a sense of urgency about this challenge and a growing realization that it is within our power to do something about it." President Barack Obama, speaking at the opening of the COP21 UN climate change conference in Paris today, Nov. 30, 2015.

HOUGHTON -- As the Paris climate change conference begins this week, it may have a special impact on Michigan Tech students and faculty and local community members who attended "A World Without Ice" -- a creative collaboration among Nobel Laureate scientist Henry Pollack (author of a book with the same title), two musicians from Ann Arbor and a multimedia artist from Amsterdam -- which took place at Michigan Tech from Sept. 24-29, 2015. The events included a lecture, a multimedia installation, class visits and campus forums, and William Kleinert's documentary film Project: Ice.*

Guy Meadows, director of Michigan Tech's Great Lakes Research Center, invited these talented visitors to offer an original way of telling the story of climate change in a language that, as Pollack pointed out, would be accessible to non-scientists, i.e., not only the campus community but the general public as well.

Stephen Rush and Michael Gould, the two musicians/composers from the University of Michigan, joined with multimedia artist Marion Traenkle in creating the installation that was exhibited in the McArdle Theatre on campus from Sept. 25 through Sept. 29.

Pictured here on the Rozsa stage with scientist Henry Pollack, right, are, from left, percussionist/composer Michael Gould, multimedia artist Marion Traenkle, and musician/composer Stephen Rush. Following Pollack's Sept. 24 lecture, he and the rest of his team explained how they worked together on the multimedia installation.

Traenkle used photos taken by scientist Pollack at both poles of the planet to create a dynamic video background for the musical piece that consisted of ice melting and dripping on seven drums and amplified from underneath, combined with electronic wind sounds composed by percussionist Gould and piano and song accompaniment by Rush.

Here is a brief video clip of what visitors to the installation, welcome to walk in anytime to watch and listen, could experience:

The "World Without Ice" multimedia installation conveys a message of climate change through sights and sounds. The installation was exhibited in Michigan Tech's McArdle Theatre from Sept. 25-29, 2015. (Video by Keweenaw Now)

In his lecture on Sept. 24 in Michigan Tech's Rozsa Center, Pollack first gave an overview of several locations on earth where ice is melting and the environmental changes that melting has caused and could cause in the future if climate change is not slowed down or reversed.

"I like ice as the purveyor of the climate change story, because ice in many ways is a very neutral witness to climate change," Pollack said. "Ice is nature's best thermometer."

"I like ice as the purveyor of the climate change story, because ice in many ways is a very neutral witness to climate change," Pollack said. "Ice is nature's best thermometer."

As he begins his Sept. 24 lecture at Michigan Tech, Nobel Laureate Henry Pollack speaks about ice as "nature's best thermometer," displaying a quote from his book, A World Without Ice.

Pollack noted Arctic and Antarctic ice are opposites, since Arctic ice is ocean surrounded by continent, while Antarctic ice is continent surrounded by ocean.

Arctic melting

"Sea ice (in the Arctic) is just a few meters thick," he said.

Pollack used a graph to illustrate the melting of Arctic ice from 1978 to 2015.

Arctic melting

"Sea ice (in the Arctic) is just a few meters thick," he said.

Pollack used a graph to illustrate the melting of Arctic ice from 1978 to 2015.

Henry Pollack displays a graph to show the decrease in the extent of Arctic Ocean sea ice in millions of square kilometers from 1978 to the present.

At the present rate of melting, he explained, the Arctic could be ice-free by the middle of this century.

Greenland is one place where ice is melting very fast. A glacier on Greenland, the Jakobshavn Glacier, is moving 40 meters a day, which is 100 times faster than the "typical glacial pace" of 100 meters a year, Pollack noted.

Permafrost, the frozen sub-surface in the Arctic, is thawing as well. Since the Arctic has been warming, the permafrost, which used to freeze in October or November, now doesn't freeze until late February or March and begins to thaw in May, Pollack explained.

Greenland is one place where ice is melting very fast. A glacier on Greenland, the Jakobshavn Glacier, is moving 40 meters a day, which is 100 times faster than the "typical glacial pace" of 100 meters a year, Pollack noted.

Permafrost, the frozen sub-surface in the Arctic, is thawing as well. Since the Arctic has been warming, the permafrost, which used to freeze in October or November, now doesn't freeze until late February or March and begins to thaw in May, Pollack explained.

"The period of time you can drive across tundra is diminishing," he said.

The thawing of permafrost also causes a volume change (ice to water), a decrease in volume leading to subsidence, which disrupts infrastructure and also releases methane, a greenhouse gas, which accelerates warming of the atmosphere.

The purple areas on this map show how permafrost is distributed in the Arctic.

Mountain Glaciers

Pollack noted the melting of the Alpine glaciers in Europe is affecting water supplies as well as recreation that depends on snow and ice.

"The ice in the Tibetan plateau and the Himalayan glaciers is a source of water for about at least a quarter of earth's population," Pollack said.

These two photos (taken in 1921 and 2009) show how the ice of the West Rongbuk Glacier near Mt. Everest has thinned more than 100 meters in about a century.

Pollack displayed this map to show the many rivers partially fed by melting Himalayan glaciers, the highest, biggest ice fields in the world. When these glaciers are gone, these rivers would lose half their flow with grievous effects on agriculture and water supplies, he noted.

Antarctica

In his book, A World Without Ice, Pollack offers this description of the ice in Antarctica:

"The Antarctic ice blanket is on average about a mile and a half thick -- at its thickest it is more than two and a half miles, about 12 Empire State Buildings stacked atop one another. And even though the surface temperature averages about -50 to -60 degrees Fahrenheit over the year, at the base of this ice pile the temperature is warm enough to melt the ice."**

During his lecture, Pollack, who has visited Antarctica several times, described the Antarctic's floating ice shelves, which are formed where the ice spills off the continent and floats on the ocean.

This photo shows the Ross Ice Shelf, which Henry Pollack described as being "about the size of France."

"The ocean that surrounds Antarctica is warming, and as a result it is having its effects on the Antarctic ice as well," Pollack said.

He added the west side of Antarctica is warming more than the rest of the continent partly because of the ocean circulation.

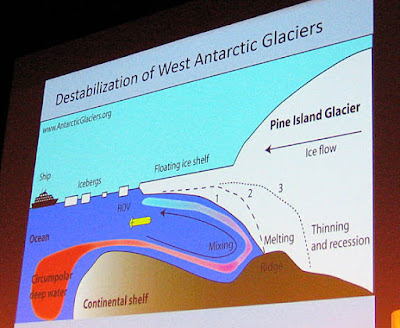

This diagram shows Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier, which Pollack said has been breaking up fairly regularly.

This slide shows how warming water moves under a floating ice shelf, destabilizes it and breaks off icebergs.

Sea level rise

"What happens when we lose ice from Antarctica and from Greenland and from mountains?" Pollack asked. "If you drop an ice cube into a beverage glass, you know that the water level is going to rise -- and the same thing happens in the global ocean."

According to Pollack, if all the ice from Greenland and Antarctica were returned to the oceans, sea level would be raised by almost 200 feet -- a situation close to the 200-250 feet of sea level rise that would mean "A World Without Ice."

A one-meter rise of sea level (possible by the end of the 21st century) would displace 100 million people -- climate refugees -- worldwide, Pollack said. Just a few of the effects on U.S. coastal areas would include the loss of Atlantic and Gulf beaches, the Everglades and the Louisiana delta and, in the West, flooding from San Francisco Bay to Sacramento.

"That is something that shows the urgency of making policy decisions that address the issue of climate change," he added.

Pollack concluded his lecture with this quotation from the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu: "If you do not change direction, you may end up where you are heading."***

Panel Discussion in Forestry

Mountain Glaciers

Pollack noted the melting of the Alpine glaciers in Europe is affecting water supplies as well as recreation that depends on snow and ice.

"The ice in the Tibetan plateau and the Himalayan glaciers is a source of water for about at least a quarter of earth's population," Pollack said.

These two photos (taken in 1921 and 2009) show how the ice of the West Rongbuk Glacier near Mt. Everest has thinned more than 100 meters in about a century.

Pollack displayed this map to show the many rivers partially fed by melting Himalayan glaciers, the highest, biggest ice fields in the world. When these glaciers are gone, these rivers would lose half their flow with grievous effects on agriculture and water supplies, he noted.

Antarctica

In his book, A World Without Ice, Pollack offers this description of the ice in Antarctica:

"The Antarctic ice blanket is on average about a mile and a half thick -- at its thickest it is more than two and a half miles, about 12 Empire State Buildings stacked atop one another. And even though the surface temperature averages about -50 to -60 degrees Fahrenheit over the year, at the base of this ice pile the temperature is warm enough to melt the ice."**

During his lecture, Pollack, who has visited Antarctica several times, described the Antarctic's floating ice shelves, which are formed where the ice spills off the continent and floats on the ocean.

This photo shows the Ross Ice Shelf, which Henry Pollack described as being "about the size of France."

"The ocean that surrounds Antarctica is warming, and as a result it is having its effects on the Antarctic ice as well," Pollack said.

He added the west side of Antarctica is warming more than the rest of the continent partly because of the ocean circulation.

This diagram shows Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier, which Pollack said has been breaking up fairly regularly.

Sea level rise

"What happens when we lose ice from Antarctica and from Greenland and from mountains?" Pollack asked. "If you drop an ice cube into a beverage glass, you know that the water level is going to rise -- and the same thing happens in the global ocean."

According to Pollack, if all the ice from Greenland and Antarctica were returned to the oceans, sea level would be raised by almost 200 feet -- a situation close to the 200-250 feet of sea level rise that would mean "A World Without Ice."

A one-meter rise of sea level (possible by the end of the 21st century) would displace 100 million people -- climate refugees -- worldwide, Pollack said. Just a few of the effects on U.S. coastal areas would include the loss of Atlantic and Gulf beaches, the Everglades and the Louisiana delta and, in the West, flooding from San Francisco Bay to Sacramento.

"That is something that shows the urgency of making policy decisions that address the issue of climate change," he added.

Pollack concluded his lecture with this quotation from the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu: "If you do not change direction, you may end up where you are heading."***

Panel Discussion in Forestry

On Sept. 25, 2015, Pollack, Rush, Gould and Traenkle led an informal panel discussion and forum at Michigan Tech's School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science.

With a backdrop announcing the opening of their multimedia installation on Sept. 25, the visiting "World Without Ice" team members discuss their work and invite students, faculty and community members to participate in a forum held at Michigan Tech's School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science.

They began by describing how they came together to create the "World Without Ice" installation, which had its origin in a class on creativity -- combining science and art -- at the University of Michigan.

Percussionist Gould said he came up with the idea of making music from ice -- made in his home freezer -- melting and dripping through holes in pizza pans onto drums. He worked with music colleague Rush to compose the score. While Pollack originally planned a slide show with his many photos of Arctic and Antarctic ice, Gould decided to improve on the slide show by inviting artist Traenkle to create a video with the photos to accompany the ice music. He had met Traenkle in Munich at a multimedia Firebird concert where he had played drums and Traenkle had done the "fantastic" visuals.

"I told Stephen and Henry we had the perfect person to make the video," Gould said.

Traenkle then spent time looking at hundreds of Pollack's photos and turned them into a video of polar ice changing that would synchronize with the musicians' melting ice musical composition.

She talked about the challenge of "giving agency to the material" and "giving space to everything."

In describing the final effect produced by the melting ice, Rush said it's actually the ice dripping at random through pizza pans and the drums that produce the score.

"The resultant score is absolutely phenomenal -- and in a certain way we're not responsible for it at all," Rush said. "It lets the materials actually perform the piece."

Pollack gave credit to Guy Meadows and his wife, Lorelle, who saw the team's first installation in Ann Arbor and invited them to bring it to Michigan Tech.

During discussion with the audience, in answer to a question on aesthetic effects of rising sea levels, Rush noted he had observed people in developing countries, whose quality of life had been seriously harmed by climate events, continue to create art, music and poetry in spite of their suffering. Rush added he believed artists have a moral obligation to call attention to the need to do something about the climate.

Pollack also noted Pope Francis is using a moral language to call attention to climate change.

"We recognize that the language of science doesn't talk to everyone," Pollack said. "The more languages you get to carry the message that climate change is serious the more people you reach. So this (installation) is an attempt to use a different language to convey an important message."

Andrew Storer, professor and associate dean of Michigan Tech's School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science, said the School has recently been trying to make more links with fine arts and other groups on campus.

"When students come into our School with their interest in natural resources one of the things that we're very aware of is that part of their interest in natural resources is related to the aesthetics of the natural resources," Storer said.

Storer invited the audience to continue the discussion with the visitors during a wine and cheese social following the forum.

Henry Pollack, pictured at far left talking to a student, and his "World Without Ice" colleagues chat with graduate students and other members of the audience following the forum in the Noblet Forestry building at Michigan Tech on Sept. 25, 2015.

During the social several Michigan Tech graduate students shared their reactions with Keweenaw Now.

Liz Ernst of Clarkston, Mich., a masters student in Forestry, said she really enjoyed the forum and definitely planned to check out the "World Without Ice" multimedia installation.

"I got an undergrad degree in earth science, so climate change and earth hazards are very interesting to me," Ernst said.

Ellen Beller of Idaho Falls, Idaho, a Ph.D. student in forest science, said her undergraduate degree was in wildlife ecology and she also planned to visit the installation.

"I thought it was a good message to combine science and art to reach a greater audience," Beller noted.

"It's a good way to get other people interested in something we're all passionate about," said Ashlee Baker of Chassell, who has a B.S. in forestry from Michigan Tech and is now working on a masters in forest science.

Kelsey Carter of Knoxville, Tenn., a Ph.D. student in forest science, said, "I hadn't thought about why climate change hasn't reached more of the population since I'm more of a data person, so it was insightful."

Ray Meininger of Marquette, who happened to be visiting Houghton, said he found out about the "World Without Ice" event from the Rozsa calendar. He attended the lecture on Sept. 24 as well as the forum in Forestry and visited the installation in Walker's McArdle Theatre.

"It's good to see science and art working together," Meininger said.

He compared Lake Superior to an ocean.

"When you look at Lake Superior you don't see the other side. You see an infinite space," he said. "You see the art and you see the vastness of the ocean."

Meininger said at first he didn't know what to make of the installation.

"But then I realized we're so small and the ice and water are so vast," he said. "The earth has gone through cycles of warming spells; but the humans, the animals and plants will suffer. I don't see any way around it."

After visiting the installation, Keweenaw Now asked other visitors their impressions as they came out of the McArdle Theatre.

"It was awesome, eerie and intense," said Sue Hill, Michigan Tech Digital Services specialist for the College of Science and Arts.

Kanak Nanavati, a local artist, said she came to see the installation because a friend of hers has explored the music.

"I thought it was meditative and calming; it was peaceful," Nanavati commented. "The music is very moving with the percussion. The sound of the ice melting and dripping gives the melody."

Film: Project: Ice, by William Kleinert

On Sunday, Sept. 27, filmmaker William Kleinert, director and executive producer, presented his documentary Project: Ice at the Rozsa Center in a free showing followed by a panel discussion.

Kleinert described the film as coming "from the crossroads of history, science, and climate change."

The film explores North America's Great Lakes, which hold twenty percent of all the fresh surface water on the planet -- a shared Canadian-American resource that holds a timely and telling story of geology, human movement, population growth, industrialization, cultural development, recreation and the profound impact people have had on the very environment they cherish and depend upon. Through historical references and interviews with Great Lakes area residents, the film depicts how the diminishing of ice on the Great Lakes over time has affected human activities from farming practices to Coast Guard responsibilities, pond hockey, tourism and ice fishing.

Kleinert, who grew up on Lake Erie, is a committed environmentalist, avid student of history and a 40-year veteran of the media business. He noted the idea of the film came to him during a circle tour of Lake Superior with his son in 2005, when they met Brian Scott Jaeschke, a graduate of Lake Superior State University with a masters degree in maritime history and marine archaeology -- who had also worked on Great Lakes freighters. Jaeschke became co-author of the film, and Henry Pollack was the science advisor.

Film discussion: Panel members see attitude changes despite climate deniers

Following the film screening, Hugh Gorman, Michigan Tech Department of Social Sciences chair and professor of environmental history and policy, joined Kleinert, Pollack and Meadows in a panel discussion of the film, fielding questions from the audience.

Pollack said, "The importance of the story that Bill tells in the movie is that when you don't have ice cover the evaporative conditions go right through the winter, and so you have year-long water loss taking place by this additional evaporation. Put an ice cover back on it and lo and behold the water levels are returning. So the importance of ice in the level of the Great Lakes is paramount."

Meadows commented that he liked the way the movie brought out the indigenous (Native American) knowledge, including the Ojibwa knowledge of currents in the Great Lakes.

Kleinert mentioned he is also doing a film about the Outer Banks of North Carolina, where he learned the North Carolina legislature has passed legislation stating that sea rise will not exceed six inches.

"I'm very very concerned that there are still these deniers and that there are deniers in positions of great influence and power," Kleinert said.

Pollack admitted there are still deniers but said he is heartened by the counter offensive that focuses on the reality, like ice -- and the real knowledge of people who live close to nature, like farmers, who are too smart to deny climate change because their congressman is a denier.

"Nature is telling us that climate is changing," Pollack said. "The realities are taking hold, and people are recognizing that climate is affecting their lives."

Pollack noted also that local governments and the private sector are seeing economic opportunities in combatting climate change or adapting to it.

"It's the economic impact that I think is convincing Congress that this is real," Meadows noted.

Meadows cited as an example the fact that such businesses as snowmobile stores and ski resorts can't receive bank loans in locations under a certain latitude. As for Lake Superior, half the water of the Great Lakes, Meadows added he sees changes in fish stocks and migration patterns and related changes in forests.

Gorman noted a difference in student attitudes at Michigan Tech as well.

"I've been teaching about climate change since I got here in 1996, and at that time if I had 40 students in class maybe three or four of them might think it's real and most of them wouldn't," Gorman said. "Gradually over time that has split so that almost all of them think it's real now and a few don't. And they are the future voters and they are the future legislators."

Asked if he is optimistic or pessimistic about the future, Pollack replied, "I am an optimist -- optimistic that we will recognize the problem, that we'll face it squarely, and with the ingenuity of humans we're going to mitigate it far faster than most people think possible."

Notes:

* University of Michigan Emeritus Professor of Geophysics Henry Pollack is co-recipient of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize with IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) colleagues and Al Gore. Gore authored the foreward to Pollack's book, A World Without Ice.

** See A World Without Ice, by Henry Pollack (Penguin Group, 2009, 2010).

*** See Chapter 8: "Choices Amid Change," in Pollack's A World Without Ice, where he also cites Lao Tzu.

No comments:

Post a Comment